We are seeking expressions of interest from cities around the world to work with DemocracyNext to make systemic changes to how decisions about urban planning are made, with deliberative and sortition (lottery)-based approaches such as Citizens’ Assemblies as a key pillar of change

Using the proposals outlined below, the goal is to partner with 3 cities over the next 2 years to design how Citizens’ Assemblies can be embedded in each unique urban context to broaden and deepen citizen participation in urban planning decision-making processes. This will require tapping into the knowledge and expertise of each particular place in order to adapt these general proposals.

Access the application portal here

Six ways to democratise city planning - Enabling thriving and healthy cities

Below is DemocracyNext's proposal outlining 6 key ways to democratise urban planning. The proposal is the product of hundreds of conversations with stakeholders in the field over the past nine months. Its contents were co-developed with an International Task Force of 15 multi-disciplinary experts, including those with expertise in political science and law, a former chief city planner, experts in deliberative democracy, urban developers, architects, and urbanists.

DemocracyNext would like to thank the many people who have contributed their time and effort to the creation of the proposals in this paper. Thank you to the members of the International Task Force who have brought their wealth of expertise and experience to the development of this work, both online and in The Hague, The Netherlands.

The central tenets of the ideas proposed here were developed together with DemocracyNext’s International Task Force on Democratising City Planning and DemocracyNext colleagues from 10-13 September 2023 involving:

The preliminary thinking was also shaped by two earlier virtual convenings which included other Members of the DemocracyNext International Task Force including:

Thank you to our funders, The National Endowment for Democracy, Open Society Foundations, and the Rockefeller Foundation, for supporting this work.

We would like to thank Adèle Vivet for the beautiful illustrations and Mona Ebdrup for the conceptual schematic drawing found in section 3.3. Icons found in Assembly diagrams made by Freepik, juicy_fish, Uniconlabs, surang, Icongeek26 - from www.flaticon.com

The terms Citizens’ Assembly, sortition, deliberation, and citizen appear regularly throughout this proposal and are key to its understanding.

Citizens’ Assembly

A Citizens’ Assembly is a group of people who are selected through sortition to be broadly representative of a community. They are convened with the aim of making shared, consensus-driven recommendations for decision makers through deliberation. Citizens’ Assemblies are sometimes called Citizens’ Juries, Panels, or Councils depending on their size and the country where they are taking place.

There are two main ingredients of a Citizens’ Assembly that differentiate it from other forms of participation and enable its effectiveness and legitimacy - these are sortition and deliberation.

For more details on the technical and practical considerations for running a Citizens’ Assembly (including how many people to invite and select, an expected budget for running an Assembly, and other key elements) refer to our Assembling an Assembly Guide here.

For more details on the technical and practical considerations for running a Citizens’ Assembly (including how many people to invite and select, an expected budget for running an Assembly, and other key elements) refer to our Assembling an Assembly Guide here.

Sortition

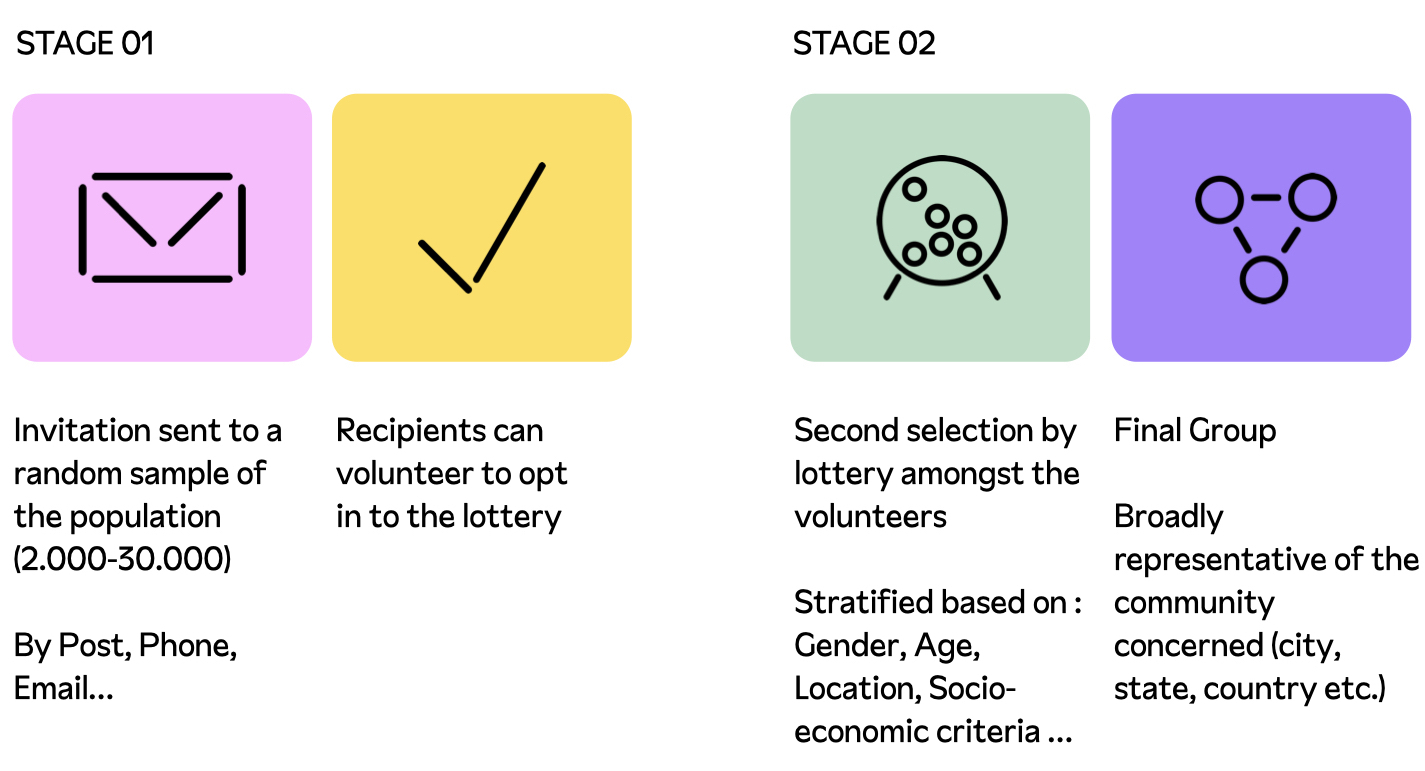

Sortition refers to a two-stage lottery selection process that brings together a broadly representative cross-section of society. In practice, this happens in two stages:

In the first stage, a large number of invitations (often between 10-30k) are sent out at random by the convening authority or organisation to people living in a city or a particular community. The invitation details why the Assembly is being convened, the issue to be addressed, how the process will work, how members will be compensated for their time and what resources are available to reduce barriers to participation (support for elder care, child care, translation during the deliberations etc), and what will happen as a result of their recommendations. People are invited to accept by confirming that they would like their name to be included in a second lottery process to choose the final group of Assembly Members.

Amongst everybody who responds positively to this first invitation, the second lottery takes place, this time with a process – known as stratification – to ensure that the final group broadly represents the community’s diversity in terms of gender, age, geography, and socio-economic differences, or other relevant criteria to the issue.

The principle of sortition means that everyone has an equal chance to represent their community as an Assembly Member, and to be represented in turn. It is a fair process for choosing a small group of people to be involved in shaping a collective decision. We cannot all be involved in every decision all the time, so there is a need for mechanisms that enable us to choose a sub-group who will dive deeply into an issue. Rotation means that the responsibility and privilege of being an Assembly Member is shared over time. It recognises that everybody has the dignity and capacity to be involved in shaping decisions affecting their lives. Bringing together a diversity of perspectives is also crucial for enabling collective intelligence to emerge.

Deliberation

Deliberation refers to weighing evidence and coming to a shared decision off the back of it. Deliberation creates the conditions to consider the complexity of the issue and to find common ground about how to tackle it. It can help unlock action where decision makers are stuck or may be facing resistance from a small portion of a community. In a Citizens’ Assembly, Members spend significant time listening,learning and collaborating through facilitated deliberation to find common ground (often 70-80% agreement) and form collective recommendations for policy makers, decision makers, and the community.

Citizen

We use the word ‘citizen’ intentionally. We mean the term in the broadest sense of a person living in a particular place, which can be in reference to a village, town, city, region, state, or country depending on the context, rather than in the more restrictive sense of ‘a legally recognised national of a state’. In this document, we use the word ‘citizen’ interchangeably with ‘people’. We see citizenship as an active practice.

Further information

Specific details about how to reach people who may not have a fixed address can also be found in section 1.5 Before the Assembly and on p.19 of FIDE’s guide on organising a democratic lottery.

1.1 Rationale for developing this proposal

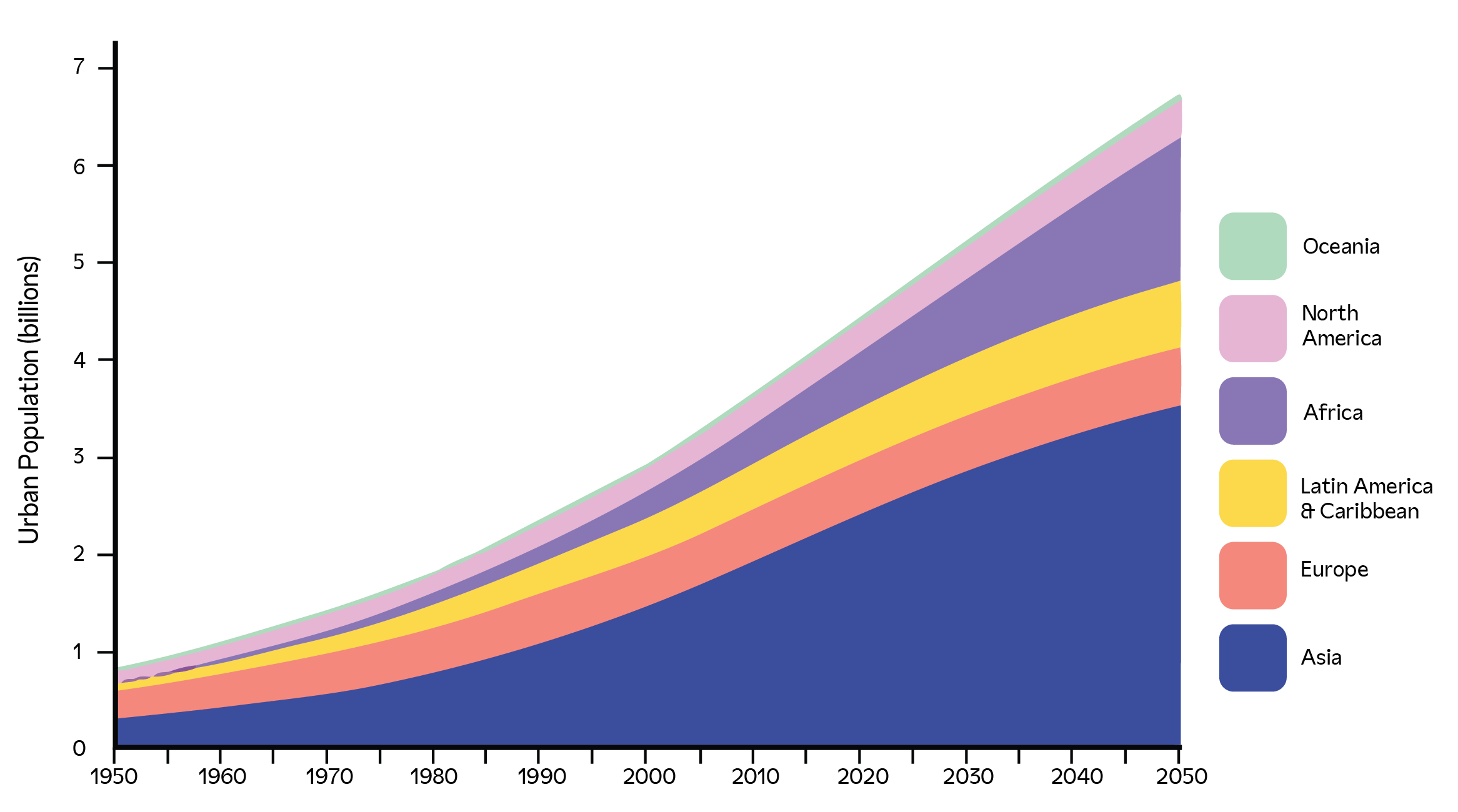

The global urban population is expected to more than double by 2050, with nearly seven in 10 people living in cities, meaning that more and more of us are directly impacted by the decisions made about our urban environments.

Around the world, urban areas are facing similar issues related to housing affordability, the widening gap of social and economic inequality, vulnerability to climate change, population increase, rapid urbanisation, and mobility challenges. These challenges are pressing and complex, and will require the collective agency and intelligence of everybody to find better, more inclusive, paths forward. For this reason, we see a huge opportunity to re-consider how people living in urban areas can be empowered to shape the places they call home.

1.2 Assembling a Task Force

We convened an International Task Force on Democratising City Planning in recognition of these problems, with a desire to propose systemic changes for addressing them. We began this work with many conversations with city councillors, officials, planners, architects, developers, and citizens in different parts of the world. They shared a frustration with the current system of urban planning.

We are not denying that there are successful and inspiring examples of participation in urban planning; there are many people around the world who have championed meaningful and innovative approaches (we highlight some of these in the appendix). But what we notice is this is not the status quo. When it happens, it often relies on the political will and imagination of those involved at one moment in time. It is not the way decisions are always taken.

th our International Task Force, we learned from numerous inspiring examples of participatory and deliberative processes around the globe (some of which are found in the Appendix). We then considered and explored how the system could change to make meaningful and informed public deliberation and participation, such as Citizens’ Assemblies, the norm in urban planning decision making.

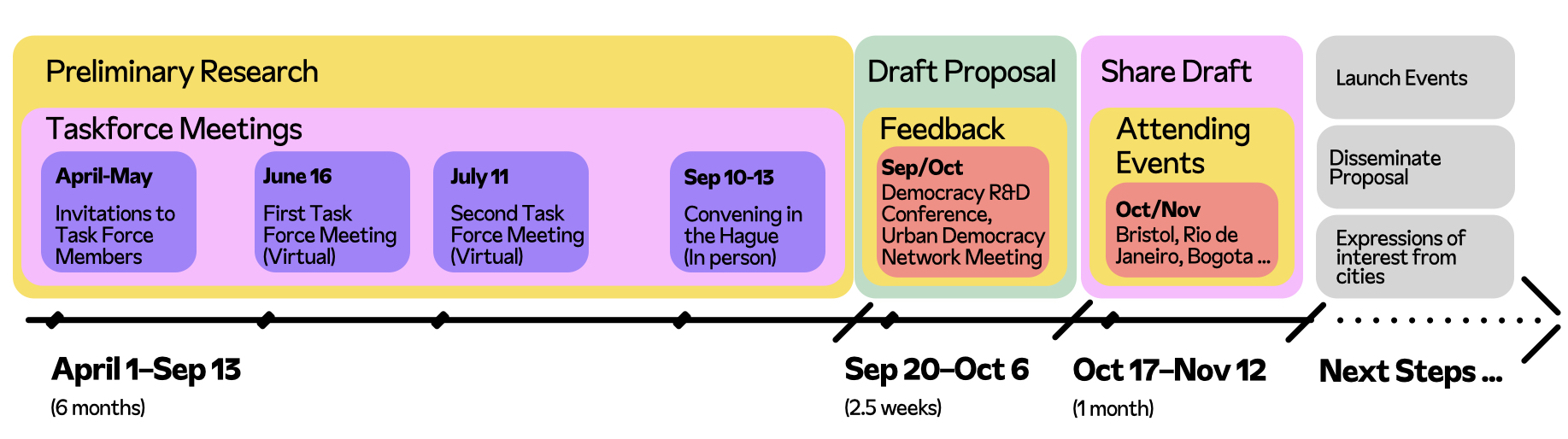

1.3 Developing the proposal

May-July 2023: During a first series of virtual meetings, we analysed the benefits and shortcomings of typical urban planning decision making processes, common participatory practices, and the challenges facing decision makers, developers, urban planners, civil society organisations, and citizens. Between these first virtual meetings, DemocracyNext attended the Urban Future conference in Stuttgart, Germany. We led a deliberative session to explore these initial ideas with a group of randomly selected participants from the conference and their feedback was integrated into the draft proposal.

September 2023: After assessing the current landscape, we held an in-person convening at DemocracyNext’s new home at the Humanity Hub in The Hague in The Hague to imagine what a more democratic city could look like and how it could be governed, followed by an iterative process of sketching out what new governance models could entail.

September-November 2023: In line with DemocracyNext’s values, we wanted this proposal to be rigorous and collaborative. We gathered feedback from a larger group of around 100 international stakeholders and experts. We convened them twice online and gathered written feedback on multiple draft versions of the document. In October and November 2023, we sought further feedback from experts from the fields of deliberative and participatory democracy at the Democracy R&D Conference in Copenhagen and the IOPD Conference in Rio de Janeiro.

2.1 What issues are cities facing?

The issues facing cities today are complex and demand solutions that draw upon the collective intelligence of society as a whole. Today, cities face a myriad of challenges and opportunities related to urban planning. For example:

2.2 How we make decisions needs to change

3.1 Introduction

More than a one-off process - changing the rules of the game for better, ongoing decision-making

The challenges that cities face today are not only a result of the specific decisions made in recent decades, but also stem from the way in which these decisions have been made. We see a need to change how people are integrated into the process of urban planning to create better, bolder, consensus-driven solutions to the complex challenges outlined above, in a way that engenders much greater legitimacy. This demands a departure from the status quo.

For more effective and inclusive decision making that enables action and gives people agency to shape their cities into thriving and healthy places, people should be able to wield greater power in shaping those decisions in an ongoing way, not only by voicing their opinions in town hall meetings, or as part of formal or mandatory consultation processes.

This proposal is not simply about improving one-off participation processes, it is about enriching and expanding how we engage with people by creating a deeper culture of engagement that can enable the conditions for a systemic, structural shift. We see this as a fundamental way to transform who decides and how decisions are made.

3.2 The importance of deeper, wider engagement

We need both depth and breadth of citizen involvement, with a holistic ecosystem of deliberative and participatory institutions that are connected directly into the key moments of urban planning decision making.

Depth is needed because the decisions concerned are complex, involving many considerations and trade-offs. Many of the challenges outlined at the outset are interconnected with one another, and there is a need to sit with that complexity rather than simplify it. It is why Citizens’ Assemblies are at the heart of the proposal outlined here – enabling a greater depth of citizen deliberation.

However, it’s necessary to connect Assembly processes with wider citizen participation to enable a breadth of community input. There are many innovative participation processes being tested internationally from which we can draw inspiration (see Appendix for examples). Directly connecting these with citizen deliberation systemically presents a great opportunity to engage both deeply and broadly.

Working in tandem with broader participation processes, Citizens’ Assemblies can strengthen and help legitimise the breadth of inputs from the community. Some examples of these include community mapping, surveys, citizen science and data-gathering initiatives, design workshops, and other relevant forms of engagement that reach a wider breadth of participants. The outputs of these participation processes can be directly linked to Citizens’ Assemblies as a way to determine the question (the remit) of the Assembly or as a form of evidence or testimony for Members to form recommendations.

3.3 A democratic planning ecosystem: Six pathways to democratising planning with three types of Assemblies

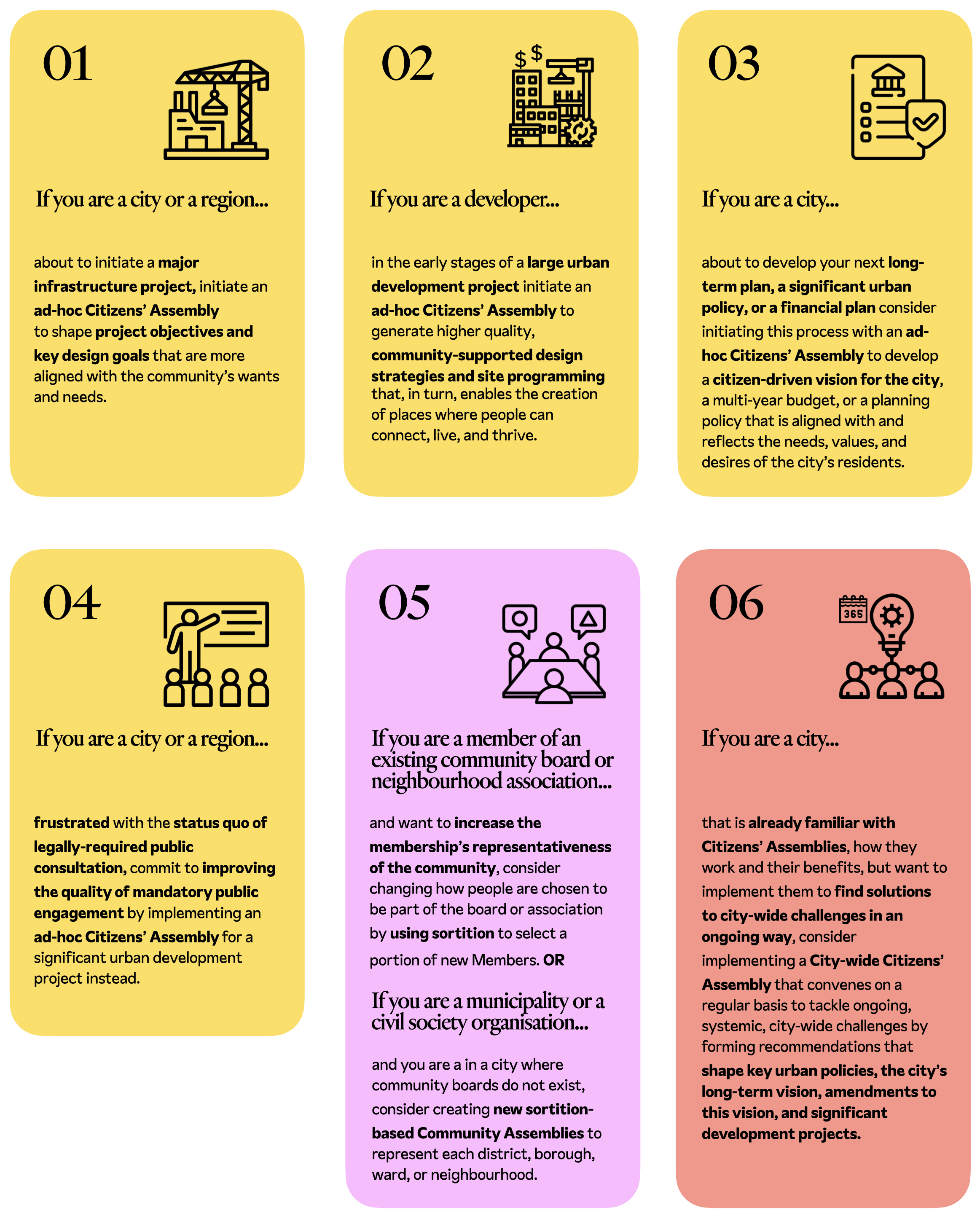

In chapter 5, we will outline six ways to democratise city planning decision making systems. Depending on a city’s current starting point, at least one, if not multiple, of these options can be seen as an initial ‘way in’ to begin making systemic changes to urban planning decision making. The six ways are outlined as different entry points:

4.1 The benefits of Citizens’ Assemblies

Why are we so focused on Citizens’ Assemblies? Why do they play a central role in this proposal? Below, we first list the general benefits of Citizens’ Assemblies followed by how these are specifically helpful in cities.

More detailed data and evidence on the benefits of Citizens’ Assemblies can be found in the OECD’s Catching the Deliberative Wave report.

4.2 Benefits for cities

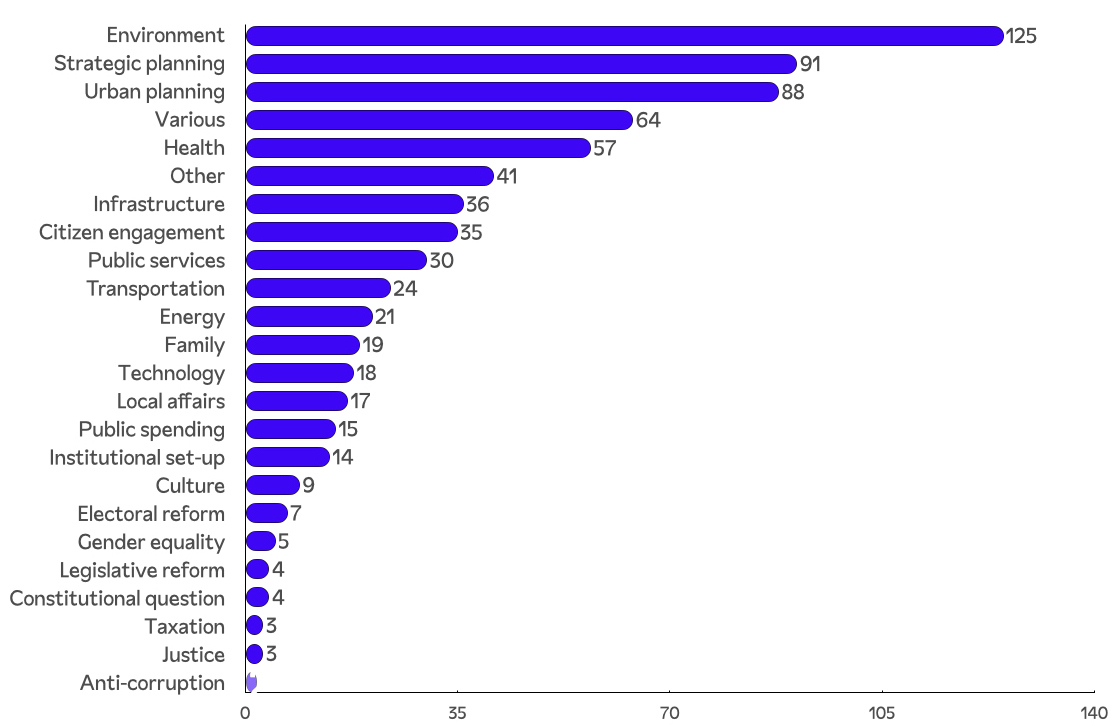

For decades, Citizens’ Assemblies have been used to address a multitude of complex issues around the world, not least questions related to urban planning (the three most commonly tackled issues are related to the environment, urban planning, and strategic planning - examples are included section 4.4).

Benefits for public authorities

By investing in high quality engagement through Citizens’ Assemblies, public authorities can avoid the high cost of a failed policy or a prolonged development process.

Benefits for developers and investors

Engaging with people in this way can help create better conditions for investment and generate more value by creating higher quality places, more resilience, and greater social cohesion.

Benefits for everyone

Citizens build an evidence base and share knowledge about their places. The result is places that are more fit for purpose.

4.3 Citizens’ Assemblies as one part of public engagement

The Assembly types detailed above cannot sit alone and separate from existing (or potential) ways of engaging with the wider public. Assembly Members might represent the diversity of society but ultimately they are a small group of people. This is why Assemblies must be connected to a wider ecosystem of engagement strategies that can run in cooperation with, and feed directly into, the Assembly process as evidence for forming recommendations. These can include (but are not limited to):

These engagement strategies can take place before the Assembly process (as a way to determine the question - the remit - of the Assembly) or during it (as a form of evidence or testimony for Members to form recommendations), while others can happen afterwards as a way to present and discuss recommendations from the Assembly with the broader public for feedback before it goes to the public authority.

The specific kinds of wider engagement strategies to implement will ultimately depend on the context and existing mechanisms for participation in a given city, the design of the Assembly itself, and the impact of the challenge to be tackled (whether it has city-wide implications or not). Designing or selecting the best kinds of participation strategies would be done in partnership with local organisations working in participation and/or municipal departments for public engagement in order to determine exactly how Citizens’ Assemblies and the wider engagement strategies can work together. For more guidance on participation strategies more broadly, we recommend the OECD’s Guidelines to Citizen Participation.

4.4 Extensive evidence of Citizens’ Assemblies used to tackle urban planning issues

In the OECD’s database of around 800 Citizens’ Assemblies that have taken place in the past four decades around the world, the three most commonly tackled issues were related to the environment, urban planning, and strategic planning. Specific issues had to do with climate change, infrastructure investment, long-term city plans, air pollution, mental health and well-being, amongst others. Some of the following examples are included in the OECD database, while others have taken place more recently.

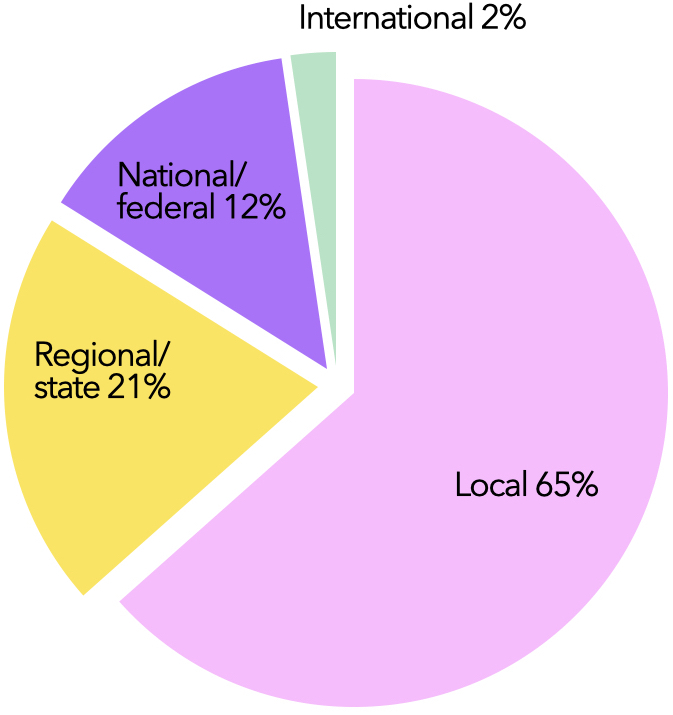

Citizens’ Assemblies have been used by various levels of government - 65% of which occur locally (OECD 2023). This is because local governments often address issues directly affecting people's daily lives, making it easier for citizens to participate and express their views compared to national issues. The lower costs of organizing local Citizens’ Assemblies also contributes to higher participation. On the next page are some of the examples from different parts of the world.

5.1 Six possible starting points

In the table and section below, we have outlined 6 possible scenarios, showing how each Assembly type can be used to address a specific challenge in the urban planning system and we include key considerations for their implementation.

While some elements of urban planning decision processes are comparable in cities across the world, we recognise that there are differences from city to city. It’s why we have started from the premise of outlining several, general, ways forward that can then be adapted to a city’s institutional, political, socio-economic, and cultural context appropriately.

The table is organised by an increasing level of embeddedness (1-6) into existing decision-making processes. For example, in some cities it may make the most sense to begin with an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly for a specific major or contentious project or area of policy development to learn from the process and then reflect on how an ongoing Citizens’ Assembly might be a logical next step to find solutions to other persistent and challenging issues. In some cities, where Citizens’ Assemblies or other forms of deep engagement have already been tested and there is momentum to continue using them, a more ambitious approach to initiating an ongoing, City--wide Assembly model could be the next step.

If a city is interested in implementing more than one Assembly, it could consider taking a multi-layered approach that holistically connects each Assembly type and the recommendations they form to feed directly into different moments of decision making. This could mean that Ad-hoc Assemblies are initiated for specific projects, while ongoing Community Assemblies and a City--wide Citizens’ Assembly provide regular input into specific urban planning decision-making processes. As outlined above, these would be supported by a dedicated Engagement Committee and other knowledge-sharing mechanisms. There are several entry points and capacity levels to consider when initiating Citizens’ Assemblies. The starting point for implementation can differ depending on numerous factors, including:

Consider implementing an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly to shape project objectives and key design goals that are more aligned with the community’s wants and needs.

Not only does this significantly reduce the risk of public pushback and criticism, it helps to avoid the high cost of a prolonged approvals process and generates greater social and economic value and community buy-in for the project in the long-term. Usually, people are left out of (or minimally consulted on) the initial stages of major decision-making processes for large-scale, multi-generation infrastructure projects. By giving people the time, space, and resources to learn about, deliberate over, and reach broad consensus on key aspects of the proposal, it's possible to increase trust in the system and deliver a better project overall.

An ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly implemented at the beginning of the decision-making process (possibly during the initial project phases involving feasibility studies, objective setting, or needs assessment) can help to shift the status-quo of typical public engagement for such developments. Of course, surveys with the public, crowdsourced community inputs (using online platforms like Decidim, change.org, make.org), or input from community dialogues must be used to include the wider public and to collect broader input which can be presented as evidence to the Assembly members to inform their final recommendations.

To ensure accountability and legitimacy, the recommendations should be publicly delivered to key decision makers, carefully considered, publicly responded to, and integrated into the project. Assembly members and the wider public must also be informed about how their specific input has shaped the decisions concerning the project, while a follow-up committee ensures that recommendations are being acted upon.

Evaluate the Assembly process and reflect on the lessons learned. Consider how implementing an ongoing City-wide Citizens’ Assembly might benefit other important developments in the future. By taking a systemic approach, it could be possible to tackle similar challenging decisions on a regular basis and gradually build greater public trust and understanding in the way we make decisions about our cities.

Consider implementing an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly to generate higher quality, community-supported design strategies and site programming that, in turn, enables the creation of places where people can connect, live, and thrive.

Not only does this reduce the risk of public opposition to the project, it frontends a deeper, engaged, and informed process of public consultation which can help speed up the approvals process, while also generating greater social and economic value for the project in the long-term. Since people are usually left out of, or minimally consulted during, the initial stages of concept development and other major decision-making moments of large-scale urban redevelopment projects, it’s understandable that they often feel disempowered. By giving people the time, space, and resources to learn about, deliberate over, and reach broad consensus on key aspects of the project from the beginning, it is possible to build more inclusive, sustainable neighbourhoods, to increase public trust in developers, and secure greater buy-in for the project.

An ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly initiated by a developer before design professionals have presented a full concept or the approvals process has begun, can help to shift the status-quo of typical public engagement for such developments. The Assembly Members can be tasked with forming the project’s sustainability goals, determining how it connects with the surrounding neighbourhood, recommending what kind of public services could be located there, or developing key design strategies for the project. Placemaking initiatives, community dialogues, surveys with the public, crowdsourced community inputs (using online platforms like Decidim, change.org, make.org) must be used to include the wider public and collect broader input to be delivered as evidence to the Assembly Members to inform their recommendations. A second stage of engagement could involve public design workshops with the broader community in collaboration with design professionals like architects, planners, and environmental consultants, to explore how the recommendations could be tangibly implemented. Technology like Fora could be leveraged to enable qualitative community inputs into the smaller, more representative Assembly process.

To ensure accountability and legitimacy, the recommendations should be publicly presented, carefully considered, publicly responded to, and integrated into the project brief. Bidding architects and other design professionals must indicate a commitment to upholding these recommendations in order to be hired. Assembly Members and the wider public must also be informed about how their specific input has shaped the decisions concerning the project, while a follow-up committee could ensure that recommendations are being acted upon.

Evaluate the Assembly to reflect on the lessons learned. Consider how using Citizens’ Assemblies on a regular basis for other large developments might benefit their success and reduce other risks. By using this model of engagement as a developer, it is possible to demonstrate what high quality public consultation looks like and how it positively impacts the project. Using Assemblies on a regular basis would also gradually build greater public trust, avoid the risk of prolonged approvals processes, and build more inclusive and sustainable neighbourhoods.

Consider initiating this process with an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly to develop a citizen-driven vision for the city, a multi-year budget, or a planning policy that is aligned with and reflects the needs, values, and desires of the city’s residents.

In this way, the Assembly process can enable the development of more socially cohesive visions, policies, and plans while avoiding the high cost of a failed policy, long-term, or financial plan that does not equitably benefit the city.

Running an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly at the beginning of these kinds of processes creates the conditions for a diverse set of perspectives, life experiences, and visions for the future to come together. The results are bolder, widely supported, ambitious plans for the future of the city. Crowdsourced community inputs (using online platforms like Decidim, change.org, make.org), surveys, and citizen science must be used to include the wider public and to collect broader input to be delivered as evidence to the Assembly members in order to inform their recommendations. These tools can also be used to present interim recommendations to the public in order to receive feedback before the Assembly Members deliver the final recommendations.

To ensure accountability and legitimacy, the recommendations should be publicly delivered to key decision makers, carefully considered, and publicly responded to. Assembly Members and the wider public must also be informed about how their specific input has shaped the decisions concerning the project, while a follow-up committee ensures that recommendations are being acted upon.

Evaluate the Assembly and reflect on the lessons learned to iterate the design for each cycle. Consider how implementing an ongoing city-wide Citizens’ Assembly might benefit the drafting of other important plans, visions, or budget questions. Perhaps a Citizens’ Assembly is convened on a regular basis to close budget holes or make amendments to the long-term plan or policy. By taking a systemic approach, it could be possible to tackle similar challenging decisions in an ongoing way and gradually build greater knowledge and capacity amongst the population to tackle these complex challenges. This can also lead to an increase in public trust and a deeper understanding of the important trade offs involved in making decisions about our cities.

Commit to improving the quality of mandatory public engagement by implementing an ad-hoc Citizens’ Assembly for a significant urban development project.

This should be done with the intention to learn from the experience in order to consider changing legislation that mandates the minimum legal requirements for public consultation to include Citizens’ Assemblies. Current public consultation is often a one-off, ‘Town Hall’ style process (and in some cases a legal obligation) that often brings out what are often called “the usual suspects” who have the time and resources to participate and voice their concerns about a particular project or policy. These meetings are usually organised in such a way that people are informed but cannot meaningfully shape the project. They also rarely represent the diversity of perspectives from across the city.

When the legal obligation for public consultation exists, it often becomes an item to ‘tick off’ when seeking approval from the planning department. Projects are generally presented to the public and they are given a choice between a few design proposals. Feedback delivered in such forums are mostly top-of-mind opinions rather than consensus-driven, thoughtfully-considered recommendations. These meetings are not designed to be constructive, and oftentimes they are not a particularly effective way of garnering constructive community inputs; there is widespread frustration with these processes by city officials, planners, developers, and citizens alike. Amending municipal or regional legislation to make Citizens’ Assemblies the go-to method (instead of relying on the typical Town Hall format of public participation) would fundamentally raise the bar of quality, impactful public consultation because:

After the process has finished, consider how changing the legislation that dictates the minimum legal requirements for public consultation to include Citizens’ Assemblies might have a positive impact on future projects across the city. This may only be for particular kinds of development projects (considering scale, budget, community impact etc), but can function as a higher quality method of engagement for challenges that need citizen input the most.

Consider changing how people are chosen to be part of the board or association by using sortition to select new Members. This would be an alternative to membership based purely on self-selection or elections; those chosen through sortition would be broadly representative of the community, and rotated on a regular basis to ensure ongoing representation. Adopting this way of selecting members could help existing boards or associations better address the needs of the diversity of residents in their community on a regular basis.

Consider creating new sortition-based Community Assemblies to represent each district, borough, ward, or neighbourhood (depending on the size/configuration of the city). These Assemblies would consist of rotating members, selected by sortition, and would be tasked to deliberate and form recommendations on specific key issues affecting their area. This means they would be responsible for choosing priority areas to implement city-wide urban policies and initiatives and could be tasked with voting on development proposals in their jurisdiction before final decision making goes to the public authority.

Community Assemblies should also work in tandem with wider public participation strategies. They can organise neighbourhood dialogues, surveys, and citizen data gathering, carry out local placemaking initiatives, or host design workshops with the public to garner feedback from the wider community. This can also help Community Assembly Members to identify key challenges and priority areas for action in their jurisdiction.

Changing the selection method for new Members in existing community bodies, or creating Community Assemblies would create the conditions for all community members to be better represented. This would help strengthen the individual and collective agency of people which can lead to better quality visions, plans, and projects for the city that are more aligned with community wants and needs.

To ensure accountability and legitimacy, there needs to be a clear, and continual, line of communication between the Community Assemblies and the public authority so that recommendations can be delivered to the right department. These should be carefully considered, publicly responded to, and integrated into projects, policies, or budgets (depending on the nature of the recommendations). Assembly Members and the wider public must also be informed about how their specific input has shaped the decisions concerning the project, while a follow-up committee ensures that recommendations are being acted upon. As a next step, consider introducing a city-wide ongoing Citizens’ Assembly that connects with the Community Assemblies and incorporates their input into recommendations with city-wide impact.

Consider implementing a city-wide Citizens’ Assembly that convenes on a regular basis to tackle ongoing, systemic, city-wide challenges by forming recommendations that shape key urban policies, the city’s long-term vision, amendments to this vision, and significant development projects. This can include some key issues such as housing and affordability, homelessness, the city’s climate policies and adaptation measures, public mobility priorities, amongst others.

People are usually left out of major decision-making processes and are not meaningfully involved in shaping the city’s vision and longer-term plan, but implementing an Assembly that convenes regularly, and is directly connected to decision making in a systemic way, could help to change this. Not only would this give people greater agency, it can help generate recommendations that can regularly feed into a decision-making process, can increase trust in the system, and result in plans or policies that are in line with what people want.

To ensure accountability and legitimacy, recommendations should always be publicly delivered to key decision makers, carefully considered, and publicly responded to. Assembly members and the wider public must also be informed about how their specific input has shaped the decisions concerning the project, while a follow-up committee ensures that recommendations are being acted upon.

Surveys with the public, crowdsourced community inputs (using online platforms like Decidim, change.org, make.org), community dialogues, design workshops, citizen science, and community mapping exercises must be used to include the wider public and to regularly collect broader input to be delivered as evidence to the Assembly members to inform their recommendations.

As a next step, consider implementing sortition-based Community Assemblies as a way to connect to the City-wide Assembly and deepen resident representation on the community level.

5.2 Can these scenarios be implemented anywhere?

The challenges of urban planning decision-making processes may differ greatly in their specifics from place to place, but many are shared in cities around the world. The actors involved, the interplay between national and local legislative and regulatory frameworks, and the stages of decision-making are sometimes quite similar. The scenarios proposed here are adaptable and can be contextualised to the particularities of a place.

We recognise that in all contexts, there is a tremendous value, and a necessity, to tap into the knowledge and expertise of a particular place in order to adapt these general proposals. There are certainly other scenarios beyond those that are outlined here which are rooted in circumstances or challenges that we have not yet considered, beyond the scope of the 100 people involved in shaping this work. While we were intentional to collaborate and sought feedback from people on all continents, we are mindful that we only heard from people in around 30 countries. There are certainly other considerations or situations that we have not necessarily thought about. However, we are prepared to learn, and wish to understand how elements of this proposal could inform an approach in such contexts.

5.3 Important considerations for all scenarios

There are two other important considerations to reflect on in all of the scenarios listed above. We see them as horizontal considerations because they have the potential to play a key role in all of the iterations outlined. One is a consideration of the physical spaces needed for Citizens’ Assemblies and the other is the necessity of including young people and children in the decisions we make about the future of our cities.

Spatial infrastructure

To accompany the systemic and procedural infrastructure for deeper and wider public engagement for urban planning, including Citizens’ Assemblies, it is important to consider the spaces in which they take place. This is crucial for enabling greater social cohesion in a community and across the city.

This can mean a number of things in terms of the spatial conditions necessary to accompany such a systemic shift. Existing community or neighbourhood organising spaces could host Community Assemblies, while the larger, less frequent, City-wide Assembly might take place in a more centralised, multi-functional community space in the city.

Many of the existing cases of Citizens’ Assemblies from around the world have taken place in the legislative chambers of local and national government buildings, in hotels, or conference centres, but there is an opportunity to reimagine and relocate where decisions about our cities are made. Current legislative spaces are not always conducive for Citizens’ Assemblies because they are not designed for deliberation. Instead, civic spaces could host Assemblies, and also connect to a wider ecosystem of community activities. Such changes could help us reconsider how and where we take important decisions about the future of our environment by placing power and decision making in closer proximity to the communities directly impacted by these decisions.

6.1 What is the minimum threshold for high quality deliberation?

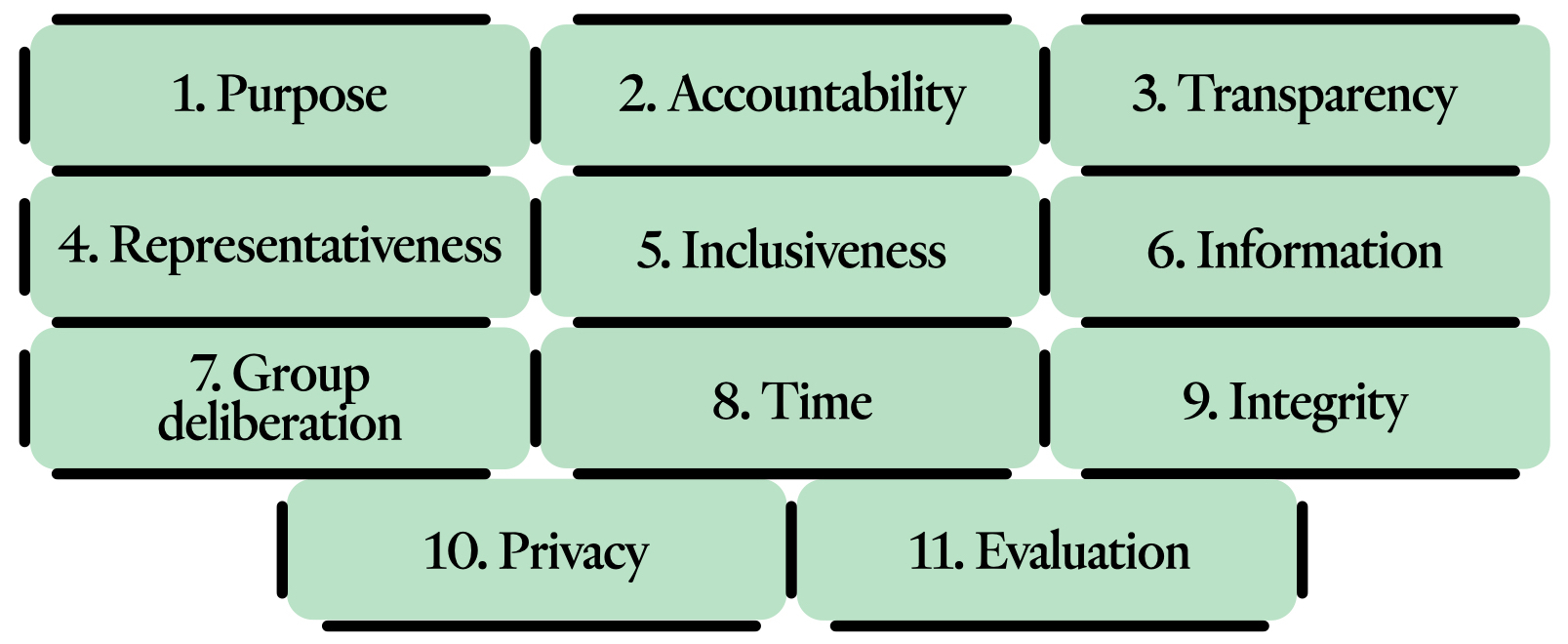

The following ‘good practice principles’ are outlined in DemocracyNext’s Assembling an Assembly Guide in section 1.1 - Conditions for Success as well as in the OECD’s Good Practice Principles for Deliberative Processes for Public Decision Making. We consider these principles as the minimum threshold for a deliberative process to be able to deliver the full benefits of a Citizens’ Assembly.

The good practice principles for running Citizens’ Assemblies have been developed based on the analysis of close to 300 examples of Assemblies in collaboration with an advisory group of leading practitioners from government, civil society, and academia. When in doubt, refer to them as guidance as to what constitutes a high quality Citizens’ Assembly. They include:

6.2 How would we know that the systemic changes we’re suggesting are successful?

7.1 Cultivating political and administrative buy-in

Getting buy-in from all relevant parties to experiment with Citizens’ Assemblies as a viable, legitimate, and worthwhile way to engage with the public is fundamental. It is important to secure cross-partisan support and work to obtain stakeholder buy-in.

7.2 Building capacity

Building capacity within municipal departments to be able to understand the value of and deliver an Assembly is a key element of ensuring success. It is equally important that recommendations can be efficiently incorporated into decision-making processes. As mentioned earlier, DemocracyNext will be launching a Citizens’ Assembly learning program for civil servants and practitioners in late 2024/early 2025. Please let us know if you are interested in participating and we will notify you when this becomes available.

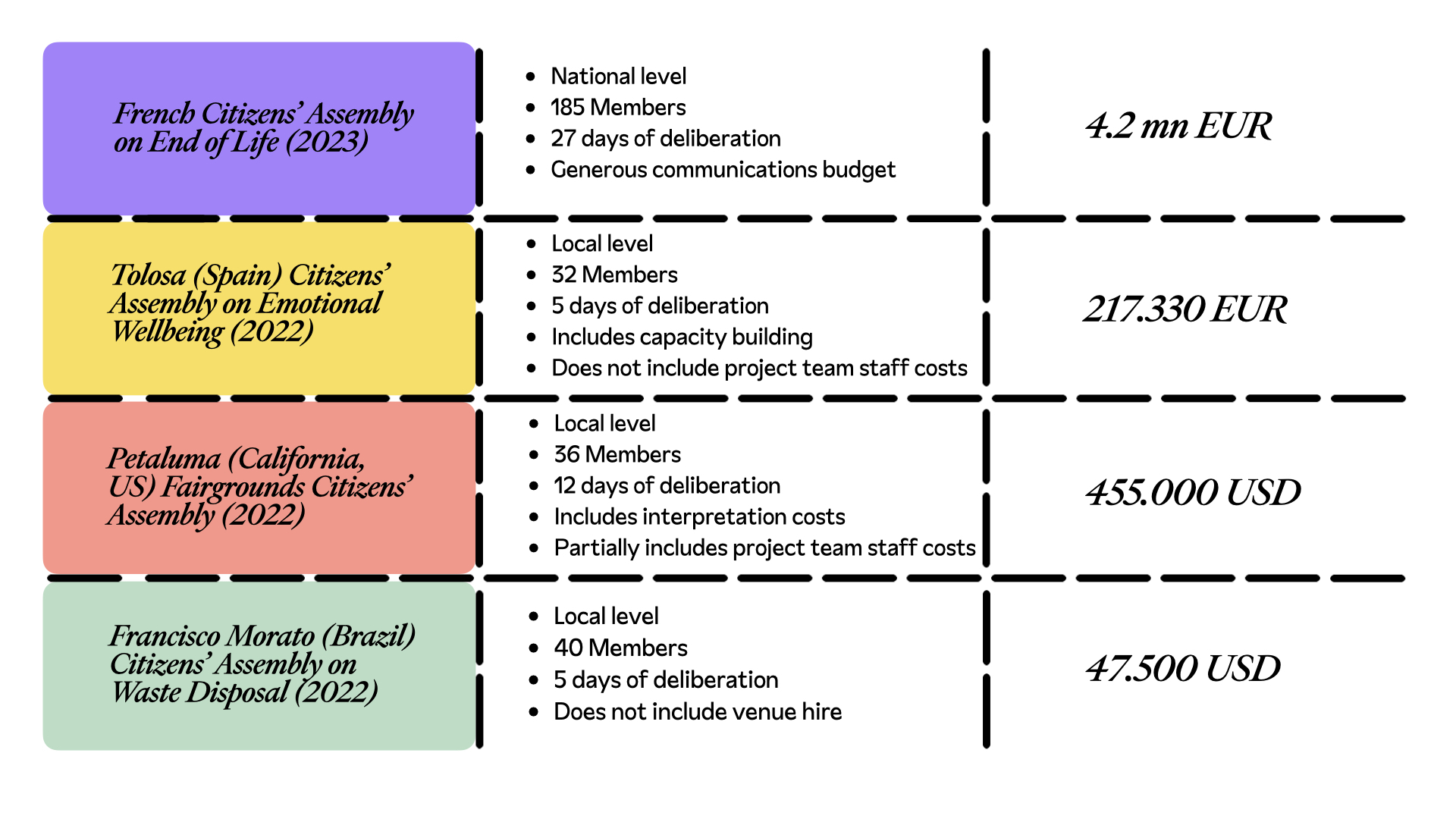

7.3 Budget considerations

Finding and allocating the necessary financial resources for municipal departments, developers, or civil society organisations to initiate and deliver a Citizens’ Assembly is not always an easy task. Below are some examples that have taken place on a local level in different parts of the world with varying budgets. The size of budget required will naturally depend on the context, size, and length of the Assembly, but these numbers can begin to provide a rough idea. It’s important to note that a significant part of the budget goes into compensating Assembly Members for their time and hiring skilled facilitators. Ongoing Assemblies reduce costs involved as they become a normal way public decisions are taken, familiar to instigators, organisers, facilitators, and citizens.

7.4 Cultivating thriving, healthy, citizen-empowered cities

We have laid out why and how making these systemic changes to the governance of urban planning decisions can help enable thriving and healthy cities. There are clear benefits to improving collaboration across the entire ecosystem of actors, as well as a huge opportunity to re-establish the status quo of participation.

There are already numerous places around the world doing this by experimenting with the ideas behind, and practices of, sortition and deliberation in order to engage with citizens both broadly and deeply. They show us that step by step, deep and transformative systemic change is possible. There is a need to start somewhere, and it’s why we have laid out six different entry points that, taken together, add up to an ambitious vision of a completely different system for urban planning decision making.

From the experience of designing and implementing Citizens’ Assemblies in different parts of the world, we have witnessed a shift in how decision makers value such processes and increase their trust in citizens, as they present thoughtful, bold, and consensus-driven solutions to some of the toughest challenges. We have also witnessed how citizens increase their trust in government, as they understand the complexity and trade-offs involved in making hard choices.

This is why we want to enable more experimentation and encourage a greater commitment to systemic shifts that embed Citizens’ Assemblies as a regular part of decision-making cycles. Only by creating deliberative spaces and providing the time and resources for people to be part of an Assembly process can we begin to make this shift more impactful.

We need to tap into the collective wisdom of the people who inhabit cities, who are experts and stakeholders in their own communities, and who bring a diversity of perspectives to the challenges cities are facing. We strongly believe people can, and should, regularly play a role in decision-making processes that affect their everyday lives, in a democratic and systemic way.

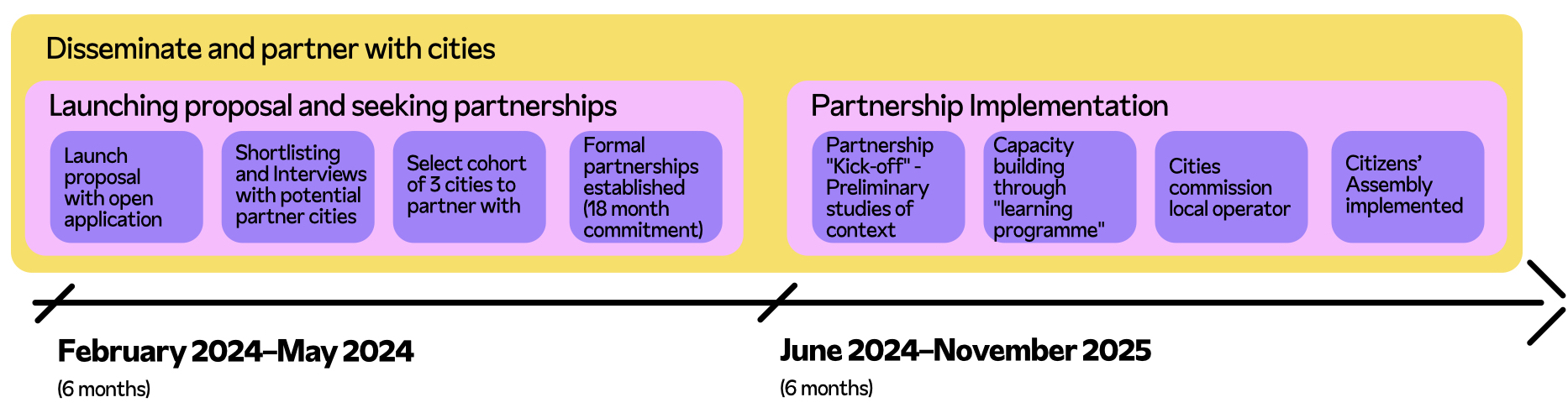

As a next step, DemocracyNext is seeking to partner with a cohort of three cities, which we will select through an open application process beginning in February 2024. Once we have established these partnerships, we will advise, and co-design with officials from each of these cities to explore and establish what is possible in their context. This will include a consideration of how specific elements of the proposal, including which kind of Assembly type and entry point is most suitable. We will also need to account for important elements such as the existing legal and regulatory frameworks for planning decisions, the city’s size and jurisdictional powers, the existing culture of public engagement, and available resources to carry out such a process.

However, this is an ongoing project. For interested cities that are not part of the first cohort in 2024, but who would like to stay updated on their progress in order to learn from these experiences, it will be possible to do so. There will also be opportunities to partner with us in the future to expand this work. Learning from one another, understanding what works, and what doesn’t, is an essential part of cultivating thriving and healthy cities with empowered citizens across the world.

Progress will be shared regularly via our website, social media platforms, and regular newsletter. If you are interested in exploring how these ideas can apply in your own city, don’t hesitate to reach out!

Nairobi - Kenya - 2017-Present

The Akiba Mashinani Trust (AMT) and its partners have been involved in the Mukuru Special Planning Area (SPA) project in Nairobi, Kenya since 2017. The project was initiated in response to eviction notices faced by the community members of Mukuru due to the improper zoning of the land they were inhabiting. AMT, in collaboration with various organisations, worked to stop the evictions and conducted research to understand the living conditions and power structures in Mukuru. This led to the initiation of a planning process to develop infrastructure and formalise the community, which took two years to persuade the county government to begin. The community was extensively involved in the research and planning phases through community meetings, radio shows, and consultation meetings.

The participation process involved the mobilisation of 41 civil society organisations, which divided the planning process into 8 planning consortiums, each focusing on a specific sector such as water, sanitation, energy, housing, and education. Residents were asked to participate in the consultation process and provide feedback on the analyzed sectors. The community members were also involved in preparing plans for each consortium and an integrated plan for the entire settlement through approximately 200 community planning forums.

Key stakeholders involved in the project included the Nairobi county government, various universities, the Kenyan federation of slum dwellers (Muungano), and the International Development Research Centre. The direct impact of the project was significant, as Mukuru was designated as a 'Special Planning Area,' which allowed for alternative planning solutions to meet the unique needs of the community. The planning process resulted in the development of 6 sector plans and the Mukuru Integrated Strategic Urban Development Plan (ISUDP). Infrastructure such as roads, electrical, sewage, and water facilities have been installed, and three hospitals and one secondary school have been developed.

The project is an ongoing, multi-year process that is still in development. The after-effects of the process have been far-reaching, with the SPA designation being viewed as a successful and necessary component of slum upgrading projects. The methodology used in Mukuru has also garnered interest in other informal settlements, both within and outside of Kenya.

The project has showcased a rare, precedent-setting opportunity for participatory upgrading partnerships at scale and has led to genuine co-planning between the community and various organizations. The SPA approach has also garnered interest from other large slum settlements in Kenya, such as Kibera and Mathare.

Related Material

How to cite this paper:

MacDonald-Nelson, James, Claudia Chwalisz, Ieva Cesnulaityte, and Lucy Reid (2024), “Six ways to democratise city planning: Enabling thriving and healthy cities”, DemocracyNext.